An account by Conrad Taylor of the May 2018 meeting of the Network for Information and Knowledge Exchange. Speakers — Hanna Chalmers of Ipsos MORI, Dr Brennan Jacoby of Philosophy at Work, and Conrad Taylor.

Fake News 1688: the ‘Popish Plot’. Titus Oates ‘revealing’ to King Charles II his totally fabricated tale of a plot to assassinate the monarch: many accused were executed.

(Listen to BBC’s ‘In Our Time’ podcast.)

Background

In the last couple of years there has been much unease about whether the news, information and opinions we find in the media can be trusted. This applies not only to the established print and broadcast media, but also the new digital media – all further echoed and amplified, or undermined, by postings, sharing, comments and trollings on social media platforms.

In the last two years, as news channels were dominated by a divisive US presidential election, and the referendum on whether Britain should leave the EU, various organisations concerned with knowledge and information have been sitting up and paying attention – in Britain, led by the Chartered Institute of Library and Information Professionals (CILIP), and the UK chapter of the International Society for Knowledge Organization (ISKO UK). The Committee of NetIKX also determined to address this issue, and so organised this afternoon seminar.

The postmodern relativism of the 1980s seems back to haunt us; the concept of expertise has been openly rubbished by politicians. Nevertheless, as information and knowledge professionals, we still tend to operate with the assumption that there are objective truths out there. Taking decisions on the basis of true facts is something we value – whether for managing our personal well-being, or contributing to democratic decision-making.

Before this seminar was given its title, the Committee referred to it as being about the problem of ‘fake news’. But as we put it together, it became more nuanced, with two complementary halves. The first half, curated by Aynsley Taylor, focused on measuring people’s trust in various kinds of media, and what this ‘trust’ thing is anyway. The second half, which I curated and included a game-like group discussion exercise, looked at causes and symptoms of misinformation in the media, and how (and with whom) we might check facts.

Ipsos MORI: a global study of trust in media

Our first speaker was Hanna Chalmers of Ipsos MORI, a global firm known to the UK public for political polling, but which has as its core business helping firms to develop viable products, testing customer expectation and experience, and doing research for government and the public sector. Hanna is a media specialist, having previously worked at the BBC, and as Head of Research at Universal Music, before switching to the agency side.

Hanna presented a ‘sneak preview’, pre-publication, of Ipsos MORI research into people’s opinions about the trustability of different forms of media. This 26-country global study had 27,000 survey respondents, and encompassed most developed markets. The company put up its own money for this, to better inform conversations with clients, and to test at scale some hypotheses they had developed internally. Hanna warned us not to regard the results as definitive; Ipsos MORI sees this as the first iteration of an ongoing enquiry, but already providing food for thought.

Issues of trust in media formerly had a low profile for commerce, but is now having an impact on many of Ipsos MORI’s clients. (Even if a company has no political stance of its own, it has good reason not to be seen advertising in or otherwise supporting media sources popularly perceived as ‘toxic brands’.)

The study’s headline findings suggest that the ‘crisis of trust in the media’ that commentators warn about may not be as comprehensive and universal as is thought. However, in the larger and more established economies, a significant proportion of respondents claim that their trust in media has declined over the last five years.

Defining ‘trust’

Trust, said Hanna, is a part of almost every interaction in everyday life. (If you buy a chicken from a supermarket, for example, you trust it has been handled properly along the supply chain.) However, what trust actually means in any given circumstance is highly dependent on context.

The Ipsos MORI team chose this working definition: Trust broadly characterises a feeling of reasonable confidence in our ability to predict behaviour. They identified two elements for further exploration, based on the ideas of Stephen MR Covey, an American author.

1. Is the action committed with a good intention? Does the other party act with our best interests at heart? In the case of a news media outlet, that would imply them acting with integrity, working towards an error-free depiction of events. However, the definition of ‘best interest’ is nowadays contentious. Many people seek news sources that reflect their own point of view, rejecting what is counter to their opinions.

2. Does the other party reliably meet their obligations? In the case of media, defining obligations is not easy. Not all media outlets aim to provide an objective serving of facts; many are undoubtedly partisan. Within new media, much blog content is opinion presented as fact; where sources are cited, they are often unreliable. The news media world is pervaded by a mix of reportage, opinion and advertising, re-written PR and spin, making media more difficult to trust than other spheres of discourse.

Why is trust in media so precarious?

Hanna invited the audience to offer possible answers to this; we responded:

- When we read a story in the news, how do we know if it is true? How can we check?

- The Web has lowered the barrier to spreading narratives and opinions. More content is being presented without going through some editorial ‘gatekeeping’ process.

- There are powerful individuals and interests who want us to distrust the media – fostering public distrust in journalism is advantageous to them.

- It’s a problem that the media uses its own definition of trust.

- Personal ‘confirmation bias’ – where people trust narrators whose opinions, beliefs, values and outlooks they share.

- The trend towards 24-hour news, and other pressures, mean that news gets rushed out without adequate fact-checking, and stripped of context.

And let’s not blame only the media. Hanna cited a 2015 study by Columbia University and the French National Institute, which found that in 59% of instances of link-sharing on social media (e.g. Facebook), the sharer had not clicked through to check out the content of the link. (See Washington Post story in The Independent, 16 June 2016.)

How the survey worked

As already described, the survey engaged in January 2018 with 27,000 people, across 26 countries, and asked about their levels of trust in the media. The sample sets were organised to be nationally representative of age, gender and educational attainment.

The questions asked included:

- To what extent, if at all, do you trust each of the following to be

a reliable source of news and information?

[See below for explanation of what ‘the following’ were.]

- How good would you say each of the following is at providing

news and information that is relevant to you?

- To what extent, if at all, do you think each of the following acts

with good intentions in providing you with news and information?

- How much, if at all, would you say your level of trust in the following

has changed in the past five years?

- How prevalent, if at all, would you say that ‘fake news’ is in

the news and information provided to you by each of the following?

(This was accompanied by a definition of ‘fake news’ as ‘often sensational

information disguised as factual news reporting’.)

‘The following’ were, for each of these questions, five different classes of information source – (a) newspapers as a class, (b) social media as a class, (c) radio television as a class, (d) people we know in real life, and (e) people whom we know only through the Internet.

(In response to questions from the audience, Hanna explained that to break it down to an assessment of trust in particular ‘titles’, e.g. trust in RT vs BBC, or trust in The Guardian vs The Daily Express, would have been too complicated. It would have also made inter-country comparisons impossible.)

In parallel, the team conducted a literature review of other studies of trust in the media.

Hanna’s observations

Perhaps the decline in trust in advanced economies is because the recent proliferation of media channels (satellite TV, social media, news websites, online search and reference sources) means we have a broader swathe of resources for fact-checking, and which expose us to alternative narratives. That doesn’t necessarily mean we trust these alternatives, but awareness of a disparity of narratives may drive greater scepticism.

But driving in the other direction, the rise of social media magnifies the ‘echo chamber’ phenomenon where people cluster around entrenched positions, consider alternative narratives to be untruths, and social polarisation increases.

With the proliferation of media channels, competition for eyes and ears, and a scramble to secure advertising revenue, even long-established media outlets are trying to do more with fewer people – and making mistakes in the process. Social media helps those mistakes and inaccuracies take on lives of their own, before they can be corrected.

‘There is a propensity for consumers to skewer brands that mess up, and remember it’ said Hanna. ‘But it also leads to less than ideal shows of transparency [by brands] after mistakes happen.’ As an example, she mentioned the Equifax credit-rating agency’s data breach of May–July 2017, when personal details of 140+ million people were hacked. It took months for Equifax to come clean about it.

Why is there more trust in the media from people with higher levels of education? Hanna suggested it may be because they are more confident in their ability to discriminate and evaluate between news sources. (Which is paradoxical, in a way, if ‘greater trust in media’ equates to ‘more critical consumption of media’ – something we later explored in discussion.)

Trust, however, remains fairly robust overall, especially in print media, and big broadcast sources such as TV and radio. The category which Ipsos MORI labelled as ‘online websites’ was trusted markedly less. (For them, this label means news and information sites not linked to a traditional publishing model – thus the ‘BBC News’ website would not be counted by Ipsos MORI as an ‘online website’.)

Carrying the study forward

Ipsos MORI wants to carry this work forward, and has set up a global workstream for it. Meanwhile, what might the media themselves take away from this study? Hanna offered these thoughts:

- Media should trust their their audiences, and be transparent about mistakes and clarifications. This does not happen enough – and it applies to advertisers as well. They forget that we are able to check facts, and are more media-savvy and better educated and sceptical than in the past.

- Media needs to be more transparent about its funding models. It was clear, when Mark Zuckerberg was being questioned by American and EU legislators, that many had no idea about how Facebook makes its money.

- Editorial and distribution teams would benefit from greater diversity. That would put more points of view in the newsroom.

In closing, Hanna quoted the American sociologist Ronald S Burt: ‘The question is not whether to trust, but who to trust’. Restoring equilibrium and strengthening trust in the media is important for democracy. She suggested that media owners and communicators need to take responsibility for the accuracy and trustability of their communications.

Questions and comments for Hanna

One audience member wondered if differing levels of trust had shown up across the gender divide. Hanna replied, across the world women display a little more trust – but it’s a smaller differential than that linked to educational attainment.

Several people expressed surprise at greater educational attainment correlating with greater trust in media – surely those better educated are more likely to be cynical (or more kindly, ‘critical’)? Claire Parry pointed out that more educated people are also statistically more likely to work in the media (or know someone who does).

But someone else suggested that the paradox is resolved if we consider that more educated people may tend more firmly to discriminate between particular publications, broadcasters and online news sources, and follow ones they trust while ignoring others. If such a person is asked, ‘how much do you trust newspapers’ and they interpret that question as ‘how much do you trust the newspapers that you yourself read’, they are more likely to answer positively. How questions are understood and reacted to by different people is, of course, a major vulnerability of survey methodologies.

This leads on to an issue which David Penfold raised, and which has been on my mind too. Is there validity in asking people how much they trust a whole category of media, when there are such huge discrepancies in quality of trustworthiness within each category?

I would certainly not be able to answer this survey. If you ask me about trusting print media, I would come back with ‘Do you mean like The Guardian or like The Daily Express or The Daily Mail? Do you mean like Scientific American or The National Enquirer?’ To lump them together and ask me to judge the trustability of a whole category feels absurd to me. Likewise, there are online information sources which I find very trustworthy, while others are execrable. Even on Facebook, I have ‘online-only friends’ who reliably point me towards science-backed information, and I have grown to trust them, while others are entertaining but purvey a lot of nonsense.

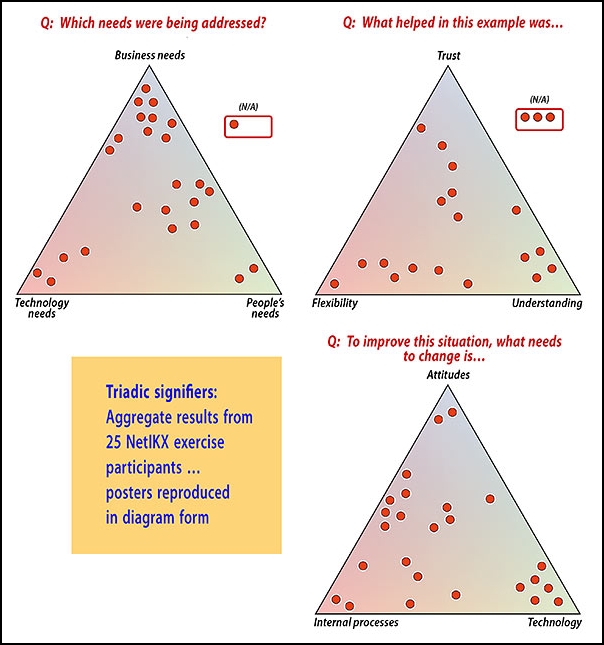

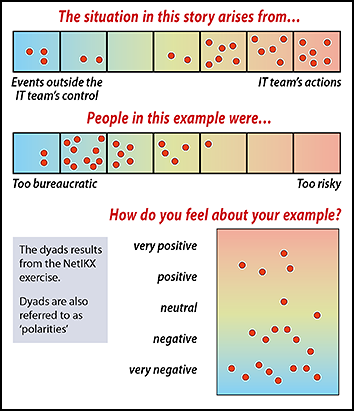

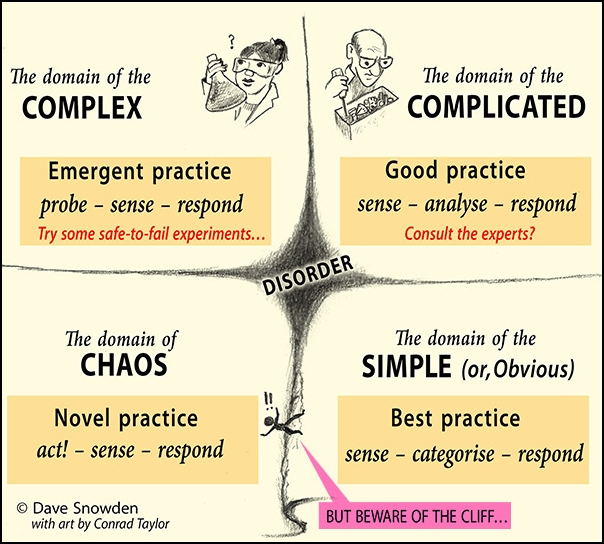

Hanna remarked that the whole project is crying out for qualitative research, to which Ainsley added ‘If someone will pay for it!’ Traditional forms of qualitative research (interviews, focus groups) are indeed expensive, but perhaps the micronarrative-plus-signifiers approach embodied in SenseMaker methodology could be tackle these questions. This can scale to find patterns in vast arrays of input, cost-effectively, and can be deployed to track ongoing trends over time. (We got a taste of how that works from Tony Quinlan at the March 2018 NetIKX meeting).

A further caveat was put forward by by David Penfold: just because a source of news and opinion is trusted, it doesn’t mean it’s right. A lot of people trusted The Daily Mail in the 1930s, when it was preaching support for Hitler and promoting anti-semitic views.

Dave Clarke thought that the survey insights were valuable; it was good to see so much quantitative data. He offered to connect the Ipsos MORI team with people he has been working with in the ‘Post-Truth’ area (of which we would hear more later that afternoon).

Martin Fowkes wondered about comparisons between very different countries and media environments. In the UK we can sample a wide spectrum of political news, but in some countries the public is fed a line supporting the leadership’s political agenda. In such conditions, if you ask these poll questions, people may ‘game and gift’ their responses, playing safe. Hanna acknowledged that problem, and suggested that each separate country could be a study in itself.

Aynsley and Hanna agreed with Dion Lindsay that this project was in the nature of a loss-leader, which might help their market to show more interest in funding further research. Also, it is important to Ipsos MORI to be able to demonstrate thought leadership to its client base through such work.

Brennan Jacoby on the philosophical basis of trust

Aynsley then introduced Dr Brennan Jacoby, whom he first saw speaking about trust at the Henley Business Centre. A philosopher by trade, Brennan would unpick what trust actually might mean.

Brennan explained that his own investigations into the concept of trust started while he was doing his doctoral work on betrayal (resulting in ‘Trust and Betrayal: a conceptual analysis’, Macquarie University 2011. Much discussion in the literature about trust contrasts trust with betrayal, but fails to define the ‘trust’ concept in the first place. In 2008, Brennan started his consulting practice ‘Philosophy at Work’. Trust was the initial focus, and remains a strong element of his work with organisations.

Brennan asked each of us to think of a brand we consider trustworthy – it could be a media brand, but not necessarily. We came up with quite a variety! – cBeebies, NHS, Nikon, John Lewis…

He told us that one time when he tried this exercise, someone shouted ‘RyanAir!’ She then explained that all RyanAir promise to do is to get you from A to B as cheaply as possible – and that they do. It seems a telling example, illustrating a breadth of interpretations around what it means to be trustworthy (is it just predictability, or is it something more?)

Critiquing the Trust Barometer

Edelman is an American public relations firm. Over the last 18 years it has published an annual ‘Trust Barometer’ report (see the current one at https://www.edelman.com/trust-barometer), which claims to measure trust around the world in government, NGOs, business, media and leaders.

(Conrad notes: there is some irony, in that Edelman has in the past acted to deflect antitrust action against Microsoft, created a fake front group of ‘citizens’ to improve WalMart’s reputation, and worked to deflect public disapproval of News Corporation’s phone hacking, oil company pollution and the Keystone XL pipeline project, amongst others.)

In the Trust Barometer 2018 report, they chose to separate ‘journalism’ from ‘media outlets’ for the first time, reflecting a growing perception that those information sources which are social platforms, such as Facebook, have been ‘hijacked’ by different causes and viewpoints and have become untrustworthy, while professional journalists may still be considered worthy of trust.

It’s interesting to see how Edelman actually asked their polling question. It went: ‘When looking for general news and information, how much would you trust each type of source for general news and information?’, followed by a list of sources, and a nine-point scale against each. Again, this survey fails to define what trust is. If we think about to the Covey definition cited by Hanna, a respondent might say, ‘Yes I trust journalists [because I think they are competent to deliver the facts]’; another respondent might say, ‘yes, I trust journalists [because I think they have good intentions].’ Someone might also say, ‘Well, I have to trust journalists, because in my country I have no choice.’

A philosophy of trust

The role of philosophy in society, said Brennan, should be to solve problems and be practical. Conceptual work isn’t merely of academic interest, but can make key distinctions which can suggest ways forward. So let’s consider the concepts of trust, trustworthiness, and finally distrust.

The word Trust can connote a spread of meanings. There’s trust in individuals, whom we meet face to face, but also those we will never meet; we may consider trust in organisations, in machinery and artefacts, or in artificial intelligence. This diversity of application may be why many conversations around trust shy away from more specificity. But a lack of specificity leaves us unable to distinguish trust from other things.

Trust may be distinguished from mere reliance. The philosophical literature agrees by and large that trust is a kind of reliance, but not just ‘mere reliance’. As an American, Brennan has no choice but to rely on Donald Trump as President – you might say count on him – given that he (Brennan) doesn’t have access to the same information and power. But Brennan doesn’t trust him. Or suppose at work you need to delegate a responsibility to someone new to the role. You have to rely on the person, but you are not quite sure you can trust them.

Special vulnerability. What distinguishes trust from mere reliance is a special kind of vulnerability. To set the scene for a thought experiment, Brennan told a story about the German philosopher Immanuel Kant (1724–1804). He was known for being obsessive about detail. The story goes that as he took his regular walk around town, the townsfolk would set the time on their clocks by the regularity of his appearance. Imagine that one day Kant sleeps in, and that day the townsfolk don’t know what time it is. They might feel annoyed, but would they feel betrayed by him? Probably not.

But now, suppose there is a town hall meeting where the citizens discuss how to be sure of the time, and Kant says, ‘Well, I take a walk at the same time each day, so you can set your clocks by me!’ But suppose one day he sleeps in or decides not to go for his walk. Now the citizens might feel let down, even betrayed. Because of Kant’s offer at the town meeting, they are not just ‘counting on’ him, they are ‘trusting’ him. They thought they had an understanding with him, which set up their expectations in a way they didn’t have before. They may say, ‘We don’t just expect that Kant will walk by at a regular time – we think he ought to.’ There is a distinction here between a predictive expectation, and what we could call a normative one.

Trust = optimistic acceptance of special vulnerability

So, Brennan suggests, we should think about trust as an acceptance of vulnerability; or more precisely, an optimistic acceptance of a special vulnerability. An ordinary kind of vulnerability might be like being vulnerable to being knocked down while crossing the road, or being caught in a rain-shower. This special vulnerability, which is the indicator of trust, is vulnerability to being betrayed by someone in a way that does us harm. There is a moral aspect to this kind of vulnerability, tied up in agreements and expectations.

Regarding the ‘optimism’ factor – suppose you need to access news from a single source, because you live in a country where the media is controlled by the State. That makes you vulnerable to whether or not you are being told the truth. You may say, ‘Well, it’s my nation’s TV station, I have to count on them.’ But suppose you have travelled to other countries and seen how differently things are arranged abroad, you may not be very optimistic about that reliance.

To sum up: Trust is when we optimistically accept our vulnerability in relying on someone.

Trust is not always a good thing!

Brennan showed a picture of a gang of criminals in New South Wales who had holed up in a house together and stayed hidden from the police, until one went to the police and betrayed the others. Did he do good or bad? Consider whistleblowing, where it can be morally positive, or there is good reason, to be distrustful or ‘treacherous’. Trust, after all, can enable abuses of power. Perhaps we should not be getting too flustered about an alleged ‘crisis of trust’ – perhaps it would not be a bad thing if trust ebbs away somewhat – because to be wary of trusting may be rational and positive.

Brennan notes, people may be thinking ‘Hey, if we are not going to trust anyone or anything, we’re not going to make it out the front door!’ But that’s only true if we think reliance and trust are exactly the same. Separating those concepts allows to get on with our lives, while retaining a healthy level of wariness and scepticism.

Baroness Onora O’Neill speaking about trust and distrust

at a TEDx event at the Houses of Parliament in June 2013.

Brennan recommended reading or listening to Baroness Onora O’Neill, an Emeritus Professor of the University of Cambridge who has written and spoken extensively on political philosophy and ethics, using a constructivist interpretation of the ethics of Kant. O’Neill places great emphasis on the importance of trust, consent, and respect for autonomy in a just society. Brennan told us that she gave a TED talk some years ago (2013), in which she argued that we should aim for appropriately placed trust (and appropriately placed distrust).

See talk video at ted.com…

Trustworthiness

When trust is appropriately placed, usually it is because it is placed in someone who is (or at least, is perceived to be) ‘trustworthy’. So what does that mean?Three things are important for trustworthiness, said Brennan; they relate quite well to Stephen MR Covey’s two points.

Competence — As the Australian moral philosopher Dr Karen Jones puts it, ‘the incompetent deserve our trust almost as little as the malicious.’ But in the sphere of media, a further distinction is useful – between technical competence and practical competence. Technical competence is the ability to do the thing that someone is counting on us for – so, will Facebook not give our details to a third party? If we expect them to prevent that, and they know that, are they competent to do so? Practical competence is, further, the ability to track the remit, to be on the same page as what one is being counted on to do.

Suppose you are away travelling, and you ask someone to look after your house while you are away. You may feel confident that they are technically competent to check on security, feed the cat, etc. You probably don’t think you need to leave a note saying ‘Please don’t paint the bathroom.’ You take it for granted that they know what it means to be a house-sitter. If you come back and find the whole place redecorated, even if you love the result, you’re not going to ask them to house-sit again.

This analogy and analysis is important in Facebook’s situation, because there has been a disconnect about what the parties are expecting. It would seem Facebook saw their relationship with us to be different from what we would have assumed. Perhaps the solution is to have a more explicit conversation about expectations.

Dion asked if these conditions of competence are not more to do with reliability than trust, and Brennan agreed. They are the preconditions for trustworthiness, but they are not sufficient.

Integrity of character — this is where the full definition of trustworthiness comes in. Reliability is all one may hope for from an animal, or a machine. Trust further involves the acceptance of a moral responsibility and commitment. Linking back to previous discussion, Brennan said that trust is a relationship that can be had only between members of ‘the moral community’. Reliability is what we expect from an autonomous vehicle; trust is what we might extend to its programmers. And programmers may be deemed to be trustworthy (or not), because they can have Character.

So if we have a media source competent at its job, and committed to doing it, we can so far only rely on them to do what we think they will always do. That is not enough to elicit trust. Assessing trustworthiness involves assessment of moral values, and integrity of character.

How do we assess ‘good character’? Many people are likely to ascribe that value to people like themselves, with whom they share an understanding of the right thing to do. We expect others to do certain things, but adding the factor of obligation clarifies things. For example, we might predict that hospitals will keep missing care targets; but additionally we expect that hospitals ought to care and not kill: this is the constitutive expectation which governs the relationship between users and services.

Brennan noted something unusual (and valuable) about how Mark Zuckerberg apologised after the recent Cambridge Analytica scandal. When most companies screw up, they apologise in a manner that responds to predictive expectations (‘we promise not to miss-sell loans again’, ‘we will never again use flammable cladding on residential buildings’). Zuckerberg’s apology said – ‘Look, sorry, we were wrong – we did the wrong thing.’ That’s valuable in building trust (if you believe him, of course): he was addressing the normative expectations. The anger that feeds the growth of distrust is driven by a sense of moral hurt – what I thought ought to have happened, didn’t.

Distrust

In his final segment, Brennan analysed the concept of distrust as involving scepticism, checking up, and ‘hard feelings’.

Showing images of President Trump and Matt Hancock (UK Secretary of State for Digital, Culture, Media and Sport) Brennan remarked: you may be sceptical about what Trump says he will do or did do; you might check up on evidence of promises and actions; you may have feelings of resentment too. As for Hancock (who also has various demerits to his reputation) – well, said Brennan, he doesn’t trust either of these men, but that doesn’t mean he distrusts both of them. He actively distrusts Trump because of his experience of the man; until recently he didn’t even know Hancock existed, so the animosity isn’t there. There’s an absence of trust, but also an absence of distrust: it’s not binary, there’s a space in the middle.

That could be significant when we talk about trusting the media, and building trust in this space. If we are going to survey or study the degree to which people trust the media, we must be careful to ensure that the questions we put to people correctly distinguish between distrust and an absence of trust; and perhaps distinguish also between mere reliance and true trust.

Perhaps in moving things forward, it may be too ambitious, or even misguided, to aim for an increase in trust? Perhaps the thing to aim for in our media and information sources is Reliability, because that is something we can check up on (e.g. fact-checking), regardless of subjective feelings of trust, distrust, or an absence of trust.

Q&A for Brennan

Bill Thompson (BBC) noted that a Microsoft researcher, danah boyd, who examined the social lives of networked teens, talks about the ‘promise’ that is made: that is, a social media network offers you a particular experience with them, and if you feel that promise has been betrayed, distrust arises. Matt Hancock had not offered Brennan anything yet… The question then is, what is the promise we would like the media to make to us, on which we could base a relationship of trust?

Brennan agreed. Do we know what expectations we have of the media? Have we tried to communicate that expectation? Have the media tried to find out? Bill replied, media owners and bosses can get very defensive very quickly, and journalists will complain that people don’t understand how tough their jobs are. But that’s no way to have a conversation!

Naomi Lees wondered about trust in the context of the inquiry into the June 2017 fire disaster at Grenfell Tower (the inquiry was about to start on a date shortly after this meeting). There is much expectation that important truths will and should be revealed. She thought that was an advance compared to the inquiry into the Hillsborough disaster, where there was a great deal of misinformation and police cover-up, and it took years for the truth to come out.

Conrad Taylor on ‘A Matter of Fact’

After a brief refreshment break, the seminar entered its second part, with a focus not so much on trust and trustworthiness, more on the integrity and truthfulness of news and factual information – both in the so-called ‘grown up media’ of print journalism and broadcasting, and the newer phenomena of web sites and social media platforms.

To open up this half of the topic, I had put together a set of slides, which has been converted to an enhanced PDF with extended page comments. It also has an appendix of 13 pages, with 80 annotated live links to relevant organisations, articles and other resources online.

I was eager to leave 50 minutes for the table-groups exercise I had devised, so my own spoken presentation had to be rushed in fifteen minutes. Because a reader can pretty much make sense of much of my presentation by downloading the prepared PDF and reading the page comments, I shall just summarise my talk briefly below.

A matter of fact, or a matter of opinion?

I started with a display of claims that have been seen in the media, particularly online. Some (‘Our rulers are shape-shifting reptilians from another planet’) are pretty wild; ‘MMR vaccine has links to autism’ has been comprehensively disproved in the medical literature; but others such as ‘Nuclear energy can never be made safe’ have been made in good faith, and are valid topics for debate.

Following events such as Russia’s annexation of Crimea, the 2016 US Presidential election, the 2017 Brexit referendum, and the war in Syria, more people and organisations have been expressing alarm at the descent into partisanship, propaganda and preposterous claims in both the established and new media. In the UK, this has included knowledge and information management organisations.

CILIP, the Chartered Institute for Library and Information Professionals, took the lead with its ‘Facts Matter’ campaign for information literacy. ISKO UK, at its September 2017 conference, hosted a panel called ‘False Narratives: developing a KO community response to post truth issues.’ (Full audio available; see links in PDF.) Dave Clarke of Synaptica ran a two-day seminar at St George’s House in January 2018 examining ‘Democracy in a Post-Truth Information Age’, and its report is also available; most recently, ISKO UK returned to the topic within a seminar on ‘Knowledge Organization and Ethics’ (again, audio available).

Dodgy news stories are not new. Rather akin to modern partisan disinformation campaigns was Titus Oates’ 1678 claim to have discovered a ‘Popish Plot’ to assassinate King Charles II (a complete fabrication, but it led to the judicial murder of a couple of dozen people).

Beyond ‘fake news’ to a better-analysed taxonomy

Cassie Staines recently argued on the blog of the fact-checking charity Full Fact that we should stop using the label ‘fake news’. She says: ‘The term is too vague to be useful, and has been weaponised by politicians.’ (Chiefly by Donald Trump, who uses it as a label to mobilise his supporters against quality newspapers and broadcasters who say things he doesn’t like). The First Draft resource site for journalists suggests a more nuanced taxonomy spanning satire and parody, misleading use of factual information by omitting or manipulating context, impersonation of genuine news sources, and completely fabricated, malicious content.

The term ‘post-truth’ got added to the Oxford English Dictionary in 2016, defined as ‘relating to or denoting circumstances in which objective facts are less influential in shaping public opinion than appeals to emotion and personal belief.’ If we want a snappy label, perhaps this one is better than ‘fake news’, and Dave Clarke appropriated it for his project the Post Truth Forum (PTF), to which I am also a recruit. PTF has attempted a more detailed two-level typology.

I briefly mentioned conspiracy theories and rumours such as ‘the 9/11 attacks were an inside job’. A 2014 article in the American Journal of Political Science, ‘Conspiracy Theories and the Paranoid Style(s) of Mass Opinion’ rejects the idea that these are unique to ignorant right-wingers, and says that there is more of a link to a ‘willingness to believe in other unseen, intentional forces and an attraction to Manichean narratives.’ (A certain tendency to conspiracy theory can also be found amongst elements on the environmentalist, left-libertarian and anarchist communities – which is not to say that everyone in those communities is a ‘conspiracist’.)

Misleading health information (anti-vaccination rumours, touting ‘alternative’ nutrition-based cancer treatments) is a category that has been characterised as a public health risk. In the case of the rubbish touted by Mike Adams’ site ‘Natural News’, there is a clearly monetised motive to sell dietary supplements.

Transparency and fact checking

Validating news in a ‘post-truth’ world brings up the question of transparency of information sources. It’s hard to check stories in the media against facts, when the facts are being covered up! Governments are past masters at the cover-up, and it is a constant political struggle to bring public service truths and data, policies and true intentions out into the open. Even then, they are subject to being deliberately misrepresented, distorted, spun and very selectively presented by politicians and partisan media. Companies have done the same, examples being Volkswagen, Carillion, Syngenta; and public relations organisations stand ready to take money to help these dodgy activities.

Karen Schriver speaks about the quest for Plain Language and transparency in American public life & business.

(Listen to podcast.)

But even when information is available, it is often not truly accessible to the public – because it may be badly organised, badly worded, badly presented – not through malice, but because of misunderstanding, incompetence and lack of communication skills. This is where information designers, plain language specialists, technical illustrators and data-diagrammers have skills to contribute. I suggest listening to a podcast of an interview with my friend Dr Karen Schriver, who was formerly Professor of Rhetoric and Document Design at Carnegie-Mellon University: she speaks about the Plain Language movement in the USA, and its prospects (again, link in PDF).

When it comes to reality checking, sometimes common sense is a good place to start. I took apart an article in London’s Evening Standard quoting a World-Wide Fund for Nature estimate that the UK uses 42 billion plastic straws annually. Do the maths! That would mean that each one of our 66 million population, from infant child to aged pensioner, on average uses 636 straws a year. Is this credible? BBC Reality Check looked into this, and a very different claim made by DEFRA (8.5 billion/year), and found that both figures came from the consultancy ‘Eunomia’, whose estimating methodologies and maths are open to question.

To be fair to journalists, it is hard for them to check facts too. In my slide deck I list a number of pressures on them. Amongst the most problematic are shrinking newsroom budgets and staffing, time pressures in the 24-hour news cycle, and more information coming in via tweets and social media and YouTube, especially from conflict and disaster zones abroad. There are projects and organisations trying to help journalists (and the public) through this maze; I have already mentioned Full Fact and First Draft, and a new one is DMINR from City University of London School of Journalism.

Group exercise: contested truths, trust in sources

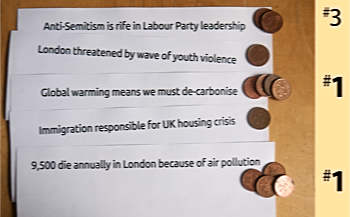

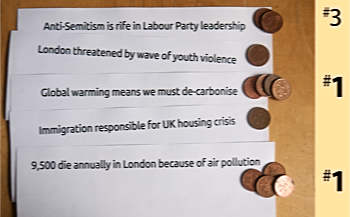

Our seminar participants gathered in table groups of about six or seven. To the tables, I distributed five sheets each bearing a headline, referring to a fairly well-known (mostly UK-centric) current affairs issue, as follows:

- Anti-Semitism is rife in Labour Party leadership

- London threatened by wave of youth violence

- Global warming means we must de-carbonise

- Immigration responsible for UK housing crisis

- 9,500 die annually in London because of air pollution

Using ‘divide the dollar’ with British pennies to rapidly select two of the topics to discuss.)

‘Divide the dollar’

I asked the teams to use a ‘divide-the-dollar’ game to quickly select two of the presented choices of topics on which their table would concentrate. (Each person took three coins, put two on their personal first choice, and one on their second choice; the group added up the result and adopted the two top scorers).

Tag and talk

I also presented a sheet of ‘tags’ denoting possible truth and comprehension issues which might afflict these narratives, such as ‘State-sponsored trolling’ or ‘hard to understand science’. Table groups were encourage to write tags onto the sheets for their chosen topics – quickly at first, without discussion – and then start deciding which of these factors were dominant in each case.

The final part of the exercise was to think about how we might start ‘fact-checking’ each news topic. Which information sources, or research methods, would you most trust in seeking clarity? Which would you definitely distrust? And finally, though in the time limit we didn’t really get into this, can people identify their own biases and filters, which might impede objective investigation of the issues?

A lively half-hour exercise ensued, with the environmental/pollution topics emerging on most tables as the favourite case studies. Problems getting to grips with the science was identified as a key difficulty in assessing claim and counter-claim about these. I then spent the last ten minutes pulling out some shared observations from the tables.

It was all a bit of a scramble, but NetIKX audiences like their chance to engage actively in small groups (it’s one of the USPs of NetIKX, which we try to do at most meetings), Perhaps it points its way to an exercise which could be repeated, if not in content, then using the same method around a different subject.

My own reflections

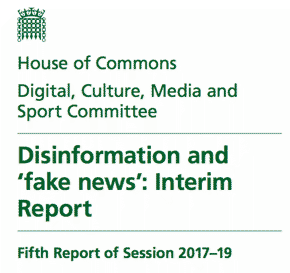

Disinformation and ‘fake news’ Interim Report. published by the House of Commons Digital, Culture, Media and Sport Committee in July 2018. The report lambasts the social media platforms, but is eerily silent about disinformation and slanted reporting in Britain’s tabloid press. (Download the report.)

I personally think that being sceptical of all sources of information is healthy, and none can demand our trust until they have earned it. This is true whatever the information channel. In that respect I agree with Brennan Jacoby, and with Baroness O’Neill.

Our seminar had focused primarily on political opinions and news stories, and in this field the control and manipulation of information is a weapon. To cope, on the one hand we need better access to fact-checking resources; on the other we need to understand the political agenda and motivations and pressures on each publisher and broadcaster — and, indeed, commercial or government or NGO entity which is trying to spin us a line.

Amongst librarians there are calls for promoting so-called ‘information literacy’ and critical thinking habits, from an early age. I would add that the related idea of ‘media literacy’ also has merit.

I have a strong interest in the field of science communication. Some of the most pressing problems of our age are best informed by science, including land and agriculture management, the treatment of diseases, climate change risks, future energy policy, and the challenges of healthcare. But here we have a double challenge: on the one hand, most people are ill-equipped to understand and evaluate what scientists say; on the other, powerful commercial and nationalist interests are working to undermine scientific truth and profit from our ignorance.

Two related aspects of science communication we might further look at are understanding risk, and understanding statistics. The information-and-knowledge gang keeps itself artificially apart from those who work with data and mathematics – that too would be a gulf worth bridging.

— Conrad Taylor, May 2018

Image of the PDF of this article, with a link

Image of the PDF of this article, with a link

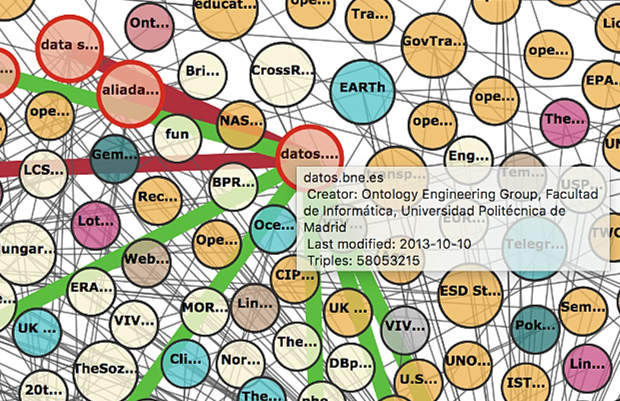

Dion is an independent consultant well known to NetIKX members. He offered us a simple introduction to graph database technology, though he avers he is no expert in the subject. He’d been feeling unclear about the differences between managing data and information, and thought one way to explore that could be to study a ‘fashionable’ topic with a bit of depth to it. He finds graph database technology exciting, and thinks data- and information-managers should be excited about it too!

Dion is an independent consultant well known to NetIKX members. He offered us a simple introduction to graph database technology, though he avers he is no expert in the subject. He’d been feeling unclear about the differences between managing data and information, and thought one way to explore that could be to study a ‘fashionable’ topic with a bit of depth to it. He finds graph database technology exciting, and thinks data- and information-managers should be excited about it too!