What next for the Web and information services? Linked data and semantic search

By Nicola Franklin

Where is the web going? That was the question the speakers at the 2nd November 2011 NetIKX seminar were aiming to answer. This join event, run with the Information for Energy Group (IFEG) and hosted at The Energy Institute, addressed the issue of linked data and the semantic web.

Whereas Web 1.0 might be thought of as ‘brochure ware’, one-way communication, and Web 2.0 has come to mean interactive, two-way communication online, the future seems to be for information and knowledge management itself to move onto the web.

The two speakers at this session described how this phenomenon is coming about, from two perspectives – Richard Wallis of Talis from the point of view of a producer or publisher of linked data onto the web, and Dr Victoria Uren of Aston University from the perspective of a researcher searching the semantic web.

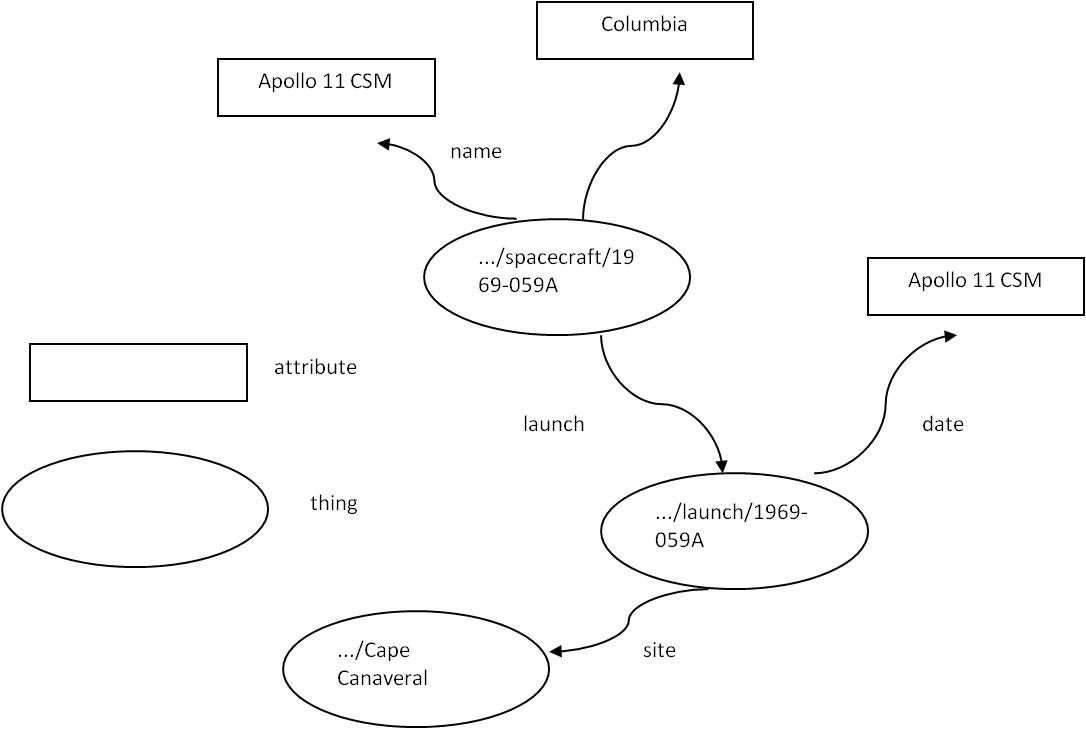

What is linked data? Richard gave an excellent introduction to the topic, leading us through a logical path to understanding how information from different data sets can be shared, merged and used online. When the web originated, it was about publishing text documents with links to other text documents, using html. Linked data is about linking ‘things’ to other ‘things’, by giving them a label or identifier (a URI). Things also have attributes, like a name, size, location, etc.

The example Richard used was a spacecraft.

A spacecraft is a ‘thing’ and can be given a label, such as:

1969-059A.

To make sure this is a unique label, some more information might be added, for example:

spacecraft/1969-059A.

To make sure people know it is your spacecraft you might add some extra information:

nasa.dataincubator.org/spacecraft/1969-059A

To store (publish) some information about this object on the internet you just at http://

http://nasa.dataincubator.org/spacecraft/1969-059A

When people start thinking about things, their attributes and how they link up together, they tend to think visually:

To transfer this into machine readable ‘computer speak’ the ovals are replaced by brackets:

<…/spacecraft/1969-059A> = a thing

name Apollo 11 CSM = an attribute and the value for that attribute

This language is called Resource Description Framework, or RDF for short.

Once common objects, or ‘things’, which are being talked about by different people, in different locations, are identified by the same RDF label, then attributes or data about those things can be merged from those different sources – the data can be linked.

This can be very powerful. For example, location data drawn from the Ordnance Survey can be linked with local authority data or central government data or NHS data. This could answer questions like “how much was spent by this organisation in that area on this service, when this party was in power?”.

An example of linked data in action can be found on the BBC nature website. This links together video archives from the BBC, information from Wikipedia, and information from other species or habitat-specific websites from various other organisations, displaying them all on one page.

Linked data can be used within an organisation, to publish data behind a firewall using intranet tools, which links together information from different business units, or held in different (perhaps incompatible) IT systems. It can also be used to publish data externally to the internet, where other people and organisations can link it to their own data – either by using the same identifiers for ’things’ in common, or by mapping between their identifier and another one used for the same ‘thing’.

Some common standards are emerging, where ontologies or naming schemas are being published and adopted to ensure that different organisations use the same identifying labels to refer to the same ‘things’. One example can be found at Schema.org, which is the standard being jointly adopted by Google, Bing and Yahoo.

How about semantic search? Victoria’s talk began from the opposite end of the spectrum – given that linked data exists on the web, how do you search for it?

Traditional online searching is based around keyword search, which uses methods such as counting words, page ranking using links, controlled form searching (eg; OPAC) or metadata. These methods were developed for searching text. To search structured data needs a different approach.

Victoria listed a range of query languages that have been developed but said that SPARQL, which was based upon SQL, was the most widely utilised. As it isn’t reasonable to expect users to familiarise themselves with a query language like this in order to carry out a search, a more friendly user interface is needed.

Again a range of methods have been developed:

- Keywords

- Forms

- Graph based

- Question answering

- Tabular browsing

Victoria described the pros and cons of each method:

Keyword searching is easy to use but is restricted to simple searches for ‘a thing’. Forms are a familiar interface, and allow more complex searches than single keywords, but forms need to be predefined and are therefore restrictive. Graph based searches give a visual representation of the data, but this is hard to do for anything more than one ontology (ie, data from one source). Natural language question answering is easy for the user, and good for heterogeneous data sets, but requires some heavy duty computing power to avoid being very slow. Tabular browsing, where you start with one keyword and are presented with a whole range of linked words to chose from to narrow the search, can be clumsy.

Victoria felt that semantic search is very good for corporate data management, where information is typically focused around one topic area and it is very useful to be able to bridge between different data silos. She gave examples of Drupal7, Virtuoso and Talis as systems that can be used for this.

Following a coffee break Syndicate Groups were set up to discuss several questions:

- What is the value to a business of using linked data and semantic search?

- Who would use the stuff from our organisation?

- What are our needs for corporate data management – what tools are needed?

I took part in one of the two tables discussing the first question. We felt that linking silos of information could help more people to find the right information, more quickly, and also to discover information they previously didn’t know existed (and therefore wouldn’t search for). This could lead to finding the people behind the information and strengthening relationships. It could also increase efficiency, raise cross-fertilisation and improve innovation.

During the group feedback session and discussion that followed, the issue of the risks of open and linked data was brought up. Could increased ease of access to some data, and the linking together of many pieces of data from different sources into one location, be misued? One example given was of insurance companies, potentially refusing to insure someone for a life or healthcare policy who they’d discovered had an unhealthy lifestyle. Another example could be terrorists making use of combined information from Ordnance Survey data + google maps + other data sets to plan atrocities.

Linked data tools and open data publishing seems to have many potential benefits and also some risks; as with any rapid change the regulation and safeguards against the risks will probably lag behind what is taking place in practice.