Working in Complexity – SenseMaker, Decisions and Cynefin

Account of a NetIKX meeting with Tony Quinlan of Narrate, 7 March 2018, by Conrad Taylor

At this NetIKX afternoon seminar, we got a very thorough introduction to Cynefin, ananalytical framework that helps decision-makers categorise problems surfacing in complex social, political and business environments. We also learned about SenseMaker®, an investigative method with software support, which can gather, manage and visualise patterns in large amounts of social intelligence, in the form of ‘narrative fragments’ with quantitative signifier data attached.

Tony Quinlan explaining how to interpret SenseMaker signifiers. The pink objects behind him are the micro-narratives we produced during the exercise, on ‘super-sticky’ Post-It notes. Photo Conrad Taylor.

The leading architect of these analytical frameworks and methods is Dave Snowden, who in 2002 set up the IBM’s Cynefin Centre for Organisational Complexity and founded the independent consultancy Cognitive Edge in 2005.

Our meeting was addressed by Tony Quinlan, CEO and Chief Storyteller of consultancy Narrate (https://narrate.co.uk/), which has been using Cognitive Edge methodology since 2008. Tony, with his Narrate colleague Meg Odling-Smee, ran some very engaging hands-on exercises for us, which gave us better insight into what SenseMaker is about. Read on!

What follows is, as usual, my personal account of the meeting, with some added background observations of my own. (I have been lucky enough to taken part in three Cognitive Edge workshops, including one in which Tony himself taught us about SenseMaker.)

The power of narrative

Tony Quinlan also used to work for IBM, in internal communications and change management; he then left to practice as an independent consultant. Around 2000, he set up Narrate, because he recognised the valuable information that is held in narratives. Then in 2005, as Dave Snowden was setting up Cognitive Edge, Tony became aware of the Cynefin Framework – a stronger theoretical basis for understanding the significance of narrative, and how one might work effectively with it.

There several ways of working with narratives in organisations, and numerous practitioners. There’s a fruitful workshop technique called ‘Anecdote Circles’, well described in a workbook from the Anecdote consultancy. (See their ‘Ultimate Guide to Anecdote Circles’ in PDF. There is also the ‘Future Backwards’ exercise, which Ron Donaldson demonstrated to NetIKX at a March 2017 meeting. These methods are good, but they require face-to-face engagement in a workshop environment.

A problem arises with narrative enquiry when you want to scale up – to collect and work with lots of narratives – hundreds, thousands, or more. How do you analyse so many narratives without introducing expert bias? Tony found that the SenseMaker approach offered a sound solution and, so far, he’s been involved in about 50 such projects, in 30 countries around the world.

I was reminded by Tony’s next comment of the words of Karl Marx: ‘The philosophers have only interpreted the world, in various ways. The point, however, is to change it.’

Tony remarked that there is quite a body of theory behind the Cognitive Edge worldview, combining narrative-based enquiry with complexity science and cognitive neuroscience insights. But the real reasons behind any SenseMaker enquiry are: ‘How do we make sense of where we are? What do we do next?’ So we were promised a highly practical focus.

A hands-on introduction to SenseMaker

Tony and Meg had prepared an exercise to give us direct experience of what SenseMaker is about, using an arsenal of stationery: markers, flip-chart pages, sticky notes and coloured spots!

Collecting narratives: The first step in a SenseMaker enquiry is to pose an open-ended question, relevant to the enquiry, to which people respond with a ‘micro-narrative’. To give us an exercise example, Tony said: ‘Sit quietly, and think of an occasion which inspired/pleased you, or frustrated you, in your use of IT [support] in your organisation (or for freelances, with an external organisation you contact to get support).’

Extra-large Post-It notes had been distributed to our tables. Following instructions, we each took one, and wrote a brief narrative about the experience we’d remembered. After that, we gave our narrative a title. We were also given sheets of sticky-backed, coloured dots. We took seven each, all of the same colour, and wrote our initials on them. We each took one of our dots, and stuck it on our own narrative sticky note. Then, we all came forward and attached our notes to the wall of the room.

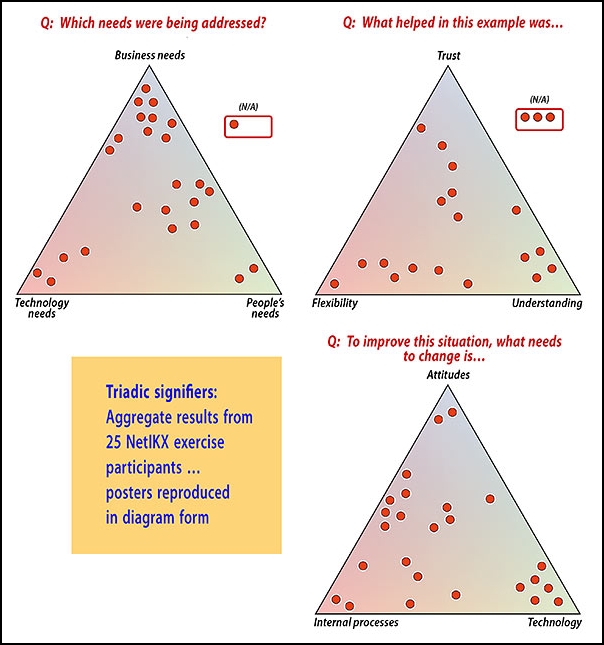

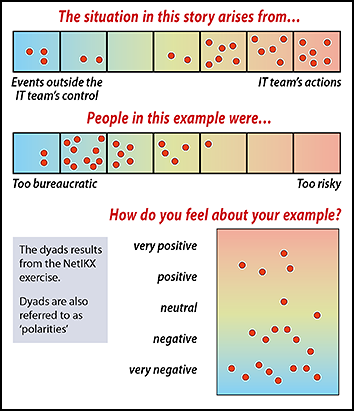

Adding signifiers: Tony now drew our attention to where he and Meg had stuck up four posters. On three, large triangles were drawn, each with a single question, and labels at the triangle corners. The fourth was drawn with three stripes, each forming a spectrum. (This description makes better sense if you look at our accompanying diagrams.) In SenseMaker practice these are called ‘triads’ and ‘dyads’ respectively, and they are both kinds of SenseMaker ‘signifiers’.

For example, the first triad asked us: ‘In the story you have written, indicate which needs were being addressed’. The three corners were labelled ‘Business needs’, ‘Technology needs’ and ‘People’s needs’. We were asked each to take one of our initialled, sticky dots and place it within the triangle, based on how strongly we felt each element was present within our story.

As for the dyads, we were to place our dot at a position along a spectrum between opposing extremes. For example, one prompted: ‘People in this example were…?’ with one end of the spectrum labelled ‘too bureaucratic’ and the other ‘too risky’.

In the diagrams below I have represented how our group’s total results plotted out over the triads and dyads, but I have made all the dots the same colour (for equal visual weight); and, obviously, there are no identifying initials.

Figure 1 Triad set

Figure 2 Dyad compilation

A few observations on the exercise

- When SenseMaker signifiers are constructed, a dyad – also referred to as a ‘polarity’ – has outer poles, which are often equally extreme opposites (‘too bureaucratic – too risky’). But in designing a triad, the corners are made equally positive, equally negative, or neutral.

- It strikes me that deciding on effective labels to use takes some considerable thought and skills, especially for triads. Over the years, Cognitive Edge has developed sets of repurposable triads and dyads, often with assistance from anthropologists.

- A real-world SenseMaker enquiry would typically have more signifier questions – perhaps six triads and two dyads.

- For practical operational reasons, we all placed our dots on a common poster. This probably means that people later in the queue were influenced by where others had already placed their dots. In a real SenseMaker implementation, each person sees a blank triangle, for their input only. Then the responses are collated (in software) across the entire dataset.

- Because the results of a SenseMaker enquiry are collated in a database, the capacity of such an enquiry is practically without limit.

- There can be further questions, e.g. to ascertain demographics. This allows for explorations of the data, such as, how do opinions of males differ from those of females? Or young people compared to their elders?

- SenseMaker results are anonymised, but the database structure in which responses are collected means that we can correlate a response on one signifier, with the same person’s response on another. For our paper exercise, we had to forgo that anonymity by using initials on coloured dots.

Our exercise gathered retrospective narratives, collected in one afternoon. But SenseMaker can be set up as an ongoing exercise, with each narrative fragment and its accompanying signifiers time-stamped. So, we can ask questions like ‘were customers more satisfied in May than in April or March?’

Analysing the results

Calling us to order, Tony talked through our results. At first, he didn’t even look at our narratives on the wall. It’s hard to assess lots of narratives without getting lost in the detail. It’s still more difficult if you have to wade through megabytes of digital audio recordings – another way some narratives have been collected in recent years.

But the signifiers can be thrown up en masse on a computer screen in a visual array, as they were on our posters. Then it’s easy to spot significant clusterings and outliers, and you can drill down to sample the narratives with a single click on a dot. Even with our small sample we could see patterns coming up. One dyad showed that most people thought the IT department was to blame for problems.

With SenseMaker software support, this can scale. Tony recalled a project in Delhi with 1,500 customers of mobile telecoms, about what helped and what didn’t when they needed support. A recent study in Jordan, about how Syrian refugees can be better supported, gathered 4,000 responses.

This was an enlightening exercise, giving NetIKX participants a glimpse of how SenseMaker works. But just a glimpse, cautioned Tony: the training course is typically three days.

Why do we do it like this?

Now it was time for some theory, including cognitive science, to explain the thinking behind SenseMaker.

How do humans make decisions? Not as rationally as we might like to believe, and not just because emotions get in the way. As humans we evolved to be pattern-matching intelligences. We scan information available to us, typically picking up just a tiny bit of what is available to us, and quickly match it against pre-stored response patterns. (And, as Dave Snowden has remarked, any of our hominid ancestors who spent too long pondering the characteristics of the leopard bounding towards them didn’t get to contribute to the gene pool!)

‘But there’s worse news,’ said Tony. ‘We don’t go for the best pattern match; we go for the first one. Then we are into confirmation bias, which is difficult to snap out of.’ (Ironically for knowledge management practice, maybe that means ‘lessons learned’ thinking can set us up for a fall – blocking us from seeing emerging new phenomena.)

Patterns of thinking are influenced by the cultures in which we are embedded, and the narratives we have heard all our lives. Those cultures and stories may be in the general social environment, or in our subcultures (e.g. religious, political, ethnic); they could be formed in the organisation in which we work; they could come at us from the media. All these influences shape what information we take in, and what we filter out; and how we respond and make decisions.

Examining people’s micro-narratives shows us the stories that people tell about their world, which shape opinions and decisions and behaviour. In SenseMaker, unlike in polls and questionnaires, we gather the stories that come to people’s minds when asked a much more open-ended prompting question. SenseMaker questions are deliberately designed to be oblique, without a ‘right answer’, thus hard to gift or game.

You don’t necessarily get clean data by asking straight questions, because there’s that strong human propensity to gift or to game – to give people the answer we think they want to hear, or to be awkward and say something to wind them up. In the Indian project with mobile service customers, when poll questions asked customers they would recommend the service to others, the responses were overwhelmingly positive. But in the SenseMaker part of the research, about 20% of those who claimed they would definitely recommend the company’s service, were shown by the triads to really think the diametric opposite.

Social research methods that do use straight questions are not without value, but they are reaching the limits of what they can do, and are often used in places where they no longer fit: where dynamics are complex, fluid and unpredictable. But complexity is not universal, said Tony; it is one domain amongst a number identified in the Cynefin Framework.

The Cynefin Framework

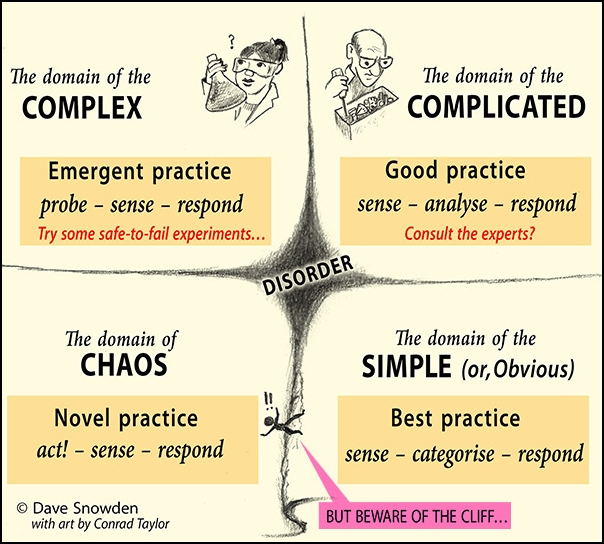

Figure 3 Diagram of the Cynefin domains, with annotations

Cynefin, explained Tony, is a Welsh word (Dave Snowden is Welsh). It means approximately ‘The place(s) where I belong.’ Cynefin is a way of making sense of the world: of human organisation primarily. It is represented by a diagram, shown in Fig. 3, and lays out a field of five ‘domains’:

- Simple. For problems in this domain, the relationship between cause and effect is obvious: if there is a problem, we all know how to fix it. (More recently, this domain is labelled ‘Obvious’, because Simple sounds like Easy. It may be Obvious we need to dig a tunnel through a mountain, but it’s not Easy…) Organisations define ‘best practice’ to tackle Obvious issues.

- Complicated. In this domain, there are repeatable and predictable chains of cause and effect, but they are not so easy to discern. A jet engine is sometimes given as a metaphorical example of such complicatedness. In this domain, problem-solving often involves the knowledge of an expert, or an analytical process.

- Chaotic. In this domain, we can’t discern a relationship between cause and effect at all, because the interacting elements are so loosely constrained. Chaos is usually a temporary condition, because a pattern will emerge, or somebody will take control and impose some sort of order. In Chaos, you don’t have time to assess carefully: decisive action is needed, in the hope that good things will emerge and can be encouraged. (And as Dave sometimes says, ‘Light candles and pray!’)

- Complex. This is a domain in which various ‘actors and factors’ – animate and inanimate – do respond to constraints, and can be attracted to influences, but those constraints and influences are relatively elastic, and there are many interactions and feedback loops that are hard to fathom. Such a system is more like a biological or ecological system than a mechanical one. Cognitive Edge practitioners have a battery of techniques for experimentation in this space, as Tony would soon describe.

- Disorder – that dark pit in the middle of the diagram represents problems where we cannot decide into which of the other domains this situation fits.

Finally, Tony pointed out a feature on the borderlands between Obvious and Chaotic, typically drawn like a cliff or fold. This is there to remind us that if people act with complete blind conviction that things are really simple and obvious, and Best Practice is followed without question, the organisation can be blindsided to major changes happening in their world. One day, when you pull the levers, you don’t get the response you have come to expect, and you have a crisis on your hands. And if you simply try to re-impose the rules, it can make things worse.

But with chaos may come opportunity. Once you have a measure of control back, you have a chance to be creative and try something new. And as we prepared to take a refreshment break, Tony urged us, ‘Don’t let a good crisis go to waste!’

Working in complex adaptive systems

Tony recalled that his MBA course was predicated on the idea that things are complicated, but there is a system for working things out. The corollary: if things don’t work out, either you didn’t plan well or you failed in implementation (‘are you lazy or stupid?’) Later, when he saw the Cynefin model, he was relieved to note that you can be neither lazy nor stupid and things can still go pear-shaped, in a situation of complexity.

In Cognitive Edge based practice, when you find you are operating in the domain of complexity, the recommendation is to initiate ‘safe-to-fail’ probes and experiments. Here are some working principles:

- Obliquity — don’t go after an intractable problem directly. A misplaced focus can have massive unintended consequences. Tony has done work around problems of radicalisation and contemporary terrorism, e.g. in Pakistan and the Middle East. Western authorities and media operate as if radicalisation was a fruit of Islamic fundamentalism – but from a Jordanian perspective, a very significant factor is when young people don’t have jobs, are bored and frustrated, and don’t have a stake in society.

- Diversity — The perspective you bring to a problem shapes how you see it. In the complex domain we can’t rely on solutions from experts alone. On the Jordanian project, to review SenseMaker inquiry results, they brought together experts from the UN, economists and government officials – but also Syrian refugees, and unemployed Jordanian youth. When the experts started to rubbish the SenseMaker data, saying it didn’t fit their experience in the field, the refugees, the youth and government officials were standing up and saying, ‘But that is our experience; we recognise it intimately.’

- Experimentation — In a complex situation you cannot predict how experiments will work out, so you try a few things at the same time. Some won’t work. That’s why probes and experiments must be safe-to-fail: if an experiment is going to fail, you don’t want catastrophic consequences; you want to pull the plug and recover quickly. (If none of your experiments fail, it probably means you have been too timid with your experimental alternatives.)

- Feedback — Experimenting in complex situations, we try to nudge and evolve the system. You don’t set up ‘a solution’ and come back in two years to see how it went – by then, things may have evolved to a point you can’t recover from. You need constant feedback to monitor the evolving situation for good or bad effects, and to spot when unexpected things happen.

When monitoring, it’s better to ask people what they do, rather than what they think. You’d be surprised how many respondents claim to a think a certain way, but that isn’t what they actually do or choose.

Even with the micro-narrative approach, you have to be careful in your evaluation. Meaning is not only in the words, and responses may be metaphorical, or even ironic. That can be tricky if you are working across cultures.

Safe-to-fail in Broken Hill: My personal favourite Snowden anecdote illustrating ‘safe-to-fail’ experiments comes from work Dave did with Meals on Wheels and the Aboriginal communities around Broken Hill, NSW, Australia. How could that community’s diets be improved to avoid Type II diabetes?

Projects were proposed by community members. 13 were judged ‘coherent’ enough to be given up to Aus$ 6,000 each: bussing elders to eat meals in common; sending troublesome youngsters to the bush to learn how to hunt; farming desert pears; farming wild yabbies (crayfish; see picture).

Results? Some flopped (bussing elders); some merged (farming desert pears and yabbies); some turned out to work synergistically (hunting lessons for youth generated a meat surplus to supply a restaurant, using traditional killing and cooking practices). Nothing failed catastrophically.

The crucial role of signifiers

In a SenseMaker enquiry, only the respondents can say what their stories mean; interacting with well designed signifiers is very powerful in this regard. Tony recalled one project with young Ethiopian women; their narratives were presented to UNDP gender experts, who were asked to read them and fill out the SenseMaker signifiers as they thought the young women might. The experts’ ideas are not unimportant; but, they significantly differed from the responses ‘from the ground’, which can be important in policymaking. SenseMaker de-privileges the expert and clarifies the voice of the respondent. Dave Snowden refers to this as ‘disintermediation’.

When you design a SenseMaker framework, you do it in such a way that it doesn’t suggest a ‘right’ answer. As an example of the latter, Tony showed a linear scale asking about a conference speaker’s presentation skills, ranging from ‘poor’ to ‘excellent’ (and looking embarrassingly like the NetIKX evaluation sheets!). ‘If I put this up, you know what answer I’m looking for.’

In contrast, he showed a triad version prepared in the course of work with a high street bank. The overall prompt asked ‘This speaker’s strengths were…’ and the three corners of the triad were marked [a] relevant information; [b] clear message; [c] good presentation skills. Tony took a sheaf of about a hundred sheets evaluating speakers at an event, and collated the ‘dots’ onto master diagrams. One speaker had provoked a big cluster of dots in the ‘relevant information’ corner. Well, relevance is good – but evidently, his talk had been unclear, and his presentation skills poor.

Tony showed a triad that was used in a SenseMaker project in Egypt. The question was, ‘What type of justice is shown in your story?’ and the corners were marked [a] revenge, getting your own back; [b] restorative, reconciling justice; and [c] deterrence, to warn others from acting as the perpetrator had done.

Tony then showed a result from a similar project in Libya, which collected about 2,000 micro-narratives. The dominant form of justice? Revenge. This was cross-correlated with responses about whether the respondents felt positively or negatively about their story, and the SenseMaker software displayed that by colouring the dots on a spectrum, green to red. And what this showed was, people felt good in that culture and context about revenge being the basis of justice.

In SenseMaker evaluation software (‘Explorer’, see end), if you want to make even more sense, you click on a dot and up comes the text of the related micro-narrative. Or, you can ask to see a range of stories in which the form of justice people felt good about was of the deterrent type. In this case, those criteria pulled up a subset of 171 stories, which the project team could then page through.

From analysis to action: another exercise

SenseMaker wasn’t created for passive social research projects. It is action-oriented. An important question used in a lot of Cognitive Edge projects is, ‘What can we do to have fewer stories like that, and more stories like this?’ That question is a useful way to encourage people to think about designing interventions, without flying away into layers of abstraction. You get stakeholders together, show them the patterns, and ask, ‘What does this mean?’ Using as a guide the idea of ‘more stories like these, fewer like those,’ you then collectively design interventions to work towards that.

Tony had more practical exercises for us, to help us to understand this analytical and intervention-designing process.

Here is the background: about five years ago, a big government organisation was worried about how its staff perceived its IT department. Tony conducted a SenseMaker exercise with about 500 participants, like the one we had done earlier – the same overall question to provoke micro-narratives, and the same or similar triad and dyad signifier questions.

Now we were divided into five table groups. Each group was given sheets of paper with labelled but blank triads on them. We were each of us to think about where on the triad we would expect most answers to have come, then make a mark on the corresponding triad. Then Tony showed us where the results actually did come in.

I’m not going into detail about how this exercise went, but it was interesting to compare our expectations as outsiders, with the actual historical results. This ‘guessing game’ is also useful to do with the stakeholder community in a real SenseMaker deployment, because it raises awareness of the divergence between perceptions and reality.

Ideas can come from the narratives

In SenseMaker, micro-narratives are qualitative data; the signifier responses, which resolve into dimensional co-ordinates, are in numerical form, which can be be more easily computed, pattern-matched, compared and visualised with the aid of machines. This assists human cognition to home in on where salient issue clusters are. Even an outsider without direct experience of the language or culture can see those patterns emerging on the chart plots.

But when it comes to inventing constructive interventions, it pays to dip down into the micro-narratives themselves, where language and culture are very important.

In a project in Bangladesh, the authorities and development agency partners had spent years trying to figure out how to encourage rural families to install latrines in their homes, instead of the prevailing behaviour of ‘open defecation’ in the fields. Tony’s initial consultations were with local experts, who said they would typically focus on one of three kinds of message. First, using family latrines improves public health, avoiding water-borne diseases and parasites. Second, it reduces risk (e.g. avoiding sexual molestation of women). Third, it reduces the disgust factor. Which of those messages would be most effective in making a house latrine a desirable thing to have?

A SenseMaker enquiry was devised, and 500 responses collected. But when the signifier patterns were reviewed, no real magic lights came on. Yes, one of the triads which asked ‘in your story, a hygienic latrine was seen as [a] healthy [b] affordable [c] desirable’ returned a strong pattern answers indicating ‘healthy’. But that could be put down to years of health campaigns – which had nevertheless not persuaded people to install latrines.

Get a latrine, have a happy marriage! But behind every dot is a story. The team in the UK asked the team in Dhaka to translate a cluster of some 19 stories from Bengali and send them over. There they found a bunch of stories which conveyed this message: if you install a latrine, you’ve got a better chance of a good marriage! One such story told of a young man, newly married, who got an ear-wigging from his mother-in-law, who told him in no uncertain terms what a low-life he was for not having a latrine in the house for her wonderful daughter…

Another story was from a village where there were many girls of marriageable age. Their families were receiving proposals from nearby villages. A young man came with his family to negotiate for a bride, and after a meal and some conversation, a guest asked to use the toilet. The girl’s father simply indicated some bushes where the family did their business. Immediately, the negotiations were broken off. The young man’s family declared that they could not establish a relationship with a family which did not have a latrine. Before long, the whole village knew why the marriage had been cancelled – and why! Shamed and chastened, the girl’s family did invest in a latrine, and the girl eventually found a husband.

As an outcome of this project, field officers have been equipped with about twenty memorable short stories, along similar lines about the positive social effect of having a latrine, and this is having an effect. If the narratives had not been mined as a resource, this would not have happened.

SenseMaker meets Cynefin

As our final exercise, Tony distributed some of the micro-narratives contributed to the project at that government organisation five years ago. We should identify issues illustrated by the narratives, and for each one we discovered, we should write a summary label on a sticky-backed note.

He placed on the wall a large poster of the Cynefin Framework diagram, and invited us to bring our notes forward, and stick them on the diagram to indicate whether we thought that problem was in the Complex domain, or Complicated, or Obvious or Chaotic, or along one of the borders… That determines whether you think there is an obvious answer, or something where experts need to consulted, or if we are in the domain of Complexity and it’s most appropriate to devise those safe-to-fail experimental interventions.

We just took five minutes over this exercise; but Tony explained, he has presided over three-hour versions of this. For the government department, he had this exercise done by groups constituted by job function: directors round one table, IT users round another, and so on. All had the same selection of micro-narratives to consider; each group interpreted them according to their shared mind-set. For the directors, just about everything was Obvious or Complicated, soluble by technical means and done by technologists. The system users considered a lot more problems to be in the Complex space, where solutions would involve improving human relations.

On that occasion, table teams were then reformulated to have a diverse mix of people, and the rearranged groups thought up direct actions that could solve the simple problems, research which could be commissioned to help solve complicated problems, and as many as forty safe-to-fail experiments to try out on complex problems. The whole exercise was complete within one day. Many of the practical suggestions which came ‘from the ground up’ were not that expensive or difficult to implement, either.

SenseMaker: some technical and commercial detail

Tony did not have time to go into the ‘nuts and bolts’ of SenseMaker, so I have done some online study to be able to tell our readers more, and give some links.

We had experienced a small exercise with the SenseMaker approach, but the real value of the methods come when deployed on a large scale, either one-off or continuously. Such SenseMaker deployments are supported by a suite of software packages and a database back end, maintained by Cognitive Edge (CE). Normally an organisation wanting to use SenseMaker would go through an accredited CE practitioner consultancy (such as Narrate), which can select the package needed, help set it up, and guide the client all the way through the process to a satisfactory outcome, including helping the client group to design appropriate interventions (which software cannot do).

SenseMaker® Collector After initial consultations with the client and the development of a signification framework, an online data entry platform called Collector is created and assigned a specific URL. Where all contributors have Internet access, for example an in-company deployment, they can directly add their stories and signifier data into an interface at that URL. Where collection is paper-based, the results will have to be manually entered later by project administrators with Internet access.

A particularly exciting recent trend in Collector is its implementation on mobile smart devices such as Apple iPad, with its multimedia capabilities. Narrative fragment capture can now be done as an audio recording with communities who cannot read or write fluently, so long as someone runs the interview and guides the signification process.

My favourite case study is one that Tony was involved in, a study in Rwanda of girls’ experience commissioned by the GirlHub project of the Nike Foundation. A cadre of local female students very quickly learned how to use tablet apps to administer the surveys; the micro-narratives were captured in audio form, stored on the device, and later uploaded to the Collector site when an Internet connection was available.

Using iPads for SenseMaker collecting: The SenseMaker Collector app for iOS was first trialled in Rwanda in 2013. Read Tony’s blog post describing how well it worked. The project as a whole was written up in 2014 by the Overseas Development Institute (‘4,000 Voices: Stories of Rwandan Girls’ Adolescence’) and the 169-page publication is available as a 10.7 MB PDF.

SenseMaker® Explorer Once all story data has been captured, SenseMaker Explorer software provides a suite of tools for data analysis. These allow for easy visual representation of data, amongst the simplest being the distribution of data points across a single triad to identify clusters and outliers (very similar to what we did with our poster exercise earlier). By drawing on multiple signifier datasets and cross-correlating them, Explorer can also produce more sophisticated data displays, for example a kind of 3D display which Dave Snowdon calls a ‘fitness landscape’ (a term probably based on a computation method used in evolutionary biology – see Wikipedia, ‘Fitness landscape’, for examples of such graphs). Explorer can also export data for analysis in other statistical packages.

A useful page to visit for an overview of the SenseMaker Suite of software is http://cognitive-edge.com/sensemaker/ — it features a short video in which Dave Snowden introduces how SenseMaker works, against a series of background images of the software screens, including on mobiles.

That page also gives links to eleven case studies, and further information about ‘SCAN’ deployments. SCANs are preconfigured, standardised SenseMaker packages around recurrent issues (example: safety), which help an organisation to implement a SenseMaker enquiry faster and more cheaply than if a custom tailored deployment is used.

Contacting Narrate

Tony and Meg have indicated that they are very happy to discuss SenseMaker deployments in more detail, and Tony has given us these contact details:

Tony Quinlan, Chief Storyteller

email:

mobile: +44 (0) 7946 094 069

Website: https://narrate.co.uk/

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!